Whose Garamond is it anyway?

Published • 25 Oct 2008Flick through various foundry catalogs for a Garamond revival or adaption and you’re bound to discover more than garalde typefaces. Interspersed amongst the many Garamonds you’ll find erroneously titled baroque faces works by another type designer, Jean Jannon. I decided to investigate the affair and while doing so swept the dust off a little history of French printing.

Prelude: the birth of French printing

The European invention of letterpress printing with movable type by Johannes Gutenberg c. 1450 systematized the Latin alphabet into individual characters that could be physically composed and reused. Because Latin letters amalgamate into an alphabet — distinct from logographies and syllabaries — they are particularly well suited to be divided, cut, and finally cast into pieces of metal type that reside in wooden cases (fig. 1.). This was the basis for the revolutionary adoption in place of the meticulous copying of books by hand word-for-word and saw the establishment of an integral part of the printing trade: typography.

Majuscules (capital letters) lived in the “upper case” whilst the minuscules (small letters) inhabited the “lower case”. This is where we draw the synonyms for upper- and lower-case from.

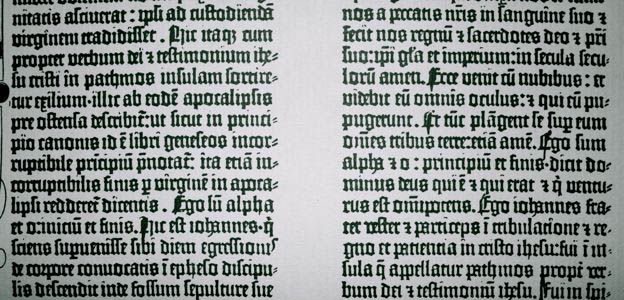

A reprint of a page of one of the Gutenberg 42-line Bibles, from Mainz, Germany. Gutenberg’s typefaces epitomize the strong gothic elements that we now classify as blackletter. The face in particular is a textura blackletter.

Fig. 1. Metal sorts being set on a composition stick with many more organised in a job case underneath. Photo by Willi Heidelbach, licensed CC-BY-SA 3.0.

A sort is a single piece of metal type, a letter of one specific typeface and size. In digital typography it has been replaced by the term glyph as digital type does not physically exist until printed. Thus a sort of Bembo italic at 12 points is distinct from another of Bembo italic 10 points. Conversely those that semantically share the same letter but are stylistically different — even if of the same family and point size — are also classified as different sorts.

The trade of printing quickly spread throughout Europe. It was introduced to France in 1470 by Johann Heynlin and Guillaume Fichet — two professors of the Sorbonne, the historic university of Paris — who enlisted the aid of German printers to establish the first printing house. Three printers from Mainz helped them construct the presses and equipment to commence cutting type. Still in the same year they printed France’s very first book, Gasparini Epistolae (“Letters”), written by the Italian grammarian Gasparino da Barizizza.

Traditional preferences

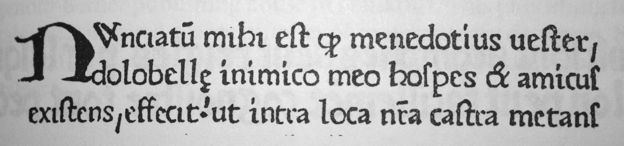

Gasparini Epistolae was set in a humanist blackletter (fig. 2). The face was a hybrid from a merging of roman and gothic elements. The style was rebuffed in favour of the traditional gothic properties of blackletter which French readers had grown accustomed to; unlike the humanist faces that were cut during the Italian Renaissance, humanist typefaces weren’t met as candidly in France as elsewhere in Europe. French typography remained moderately conservative, utilizing heavy blackletter faces of one style or another to set most printed material until the turn of the century.

Fig. 2. A sample of the humanist blackletter hybrid from Gasparini Epistolae, Haralambous, Y., 2007, Fonts & Encodings (p. 375), English edition, O’Reilly Media Inc., California, USA.

There are two noteworthy interludes between the end of the 15th century and the cutting of garalde faces in the early 16th century. In 1477 came the first book printed in French, an unusual and controversial venture as French was considered too vulgar to be set in print. Typically Latin was used for the written word, even in Germany at the time. It was set in cute bastarda (or Schwabacher) by Pasquier Bonhomme. Then in 1529 Geofrey de Troy, the personal printer to King François I, took the next steps that led to the broader adoption of roman through the printing of his book, Le Champ Fleury in which he put forth his theory that letter forms and the human anatomy are closely linked.

The Garalades and Garamond

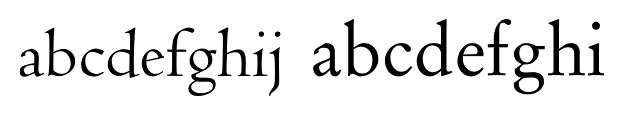

By the mid 16th century printing was a solid industry. Certainly printing was still expensive, however it had become more economically viable and less time-consuming than the the previous option of employing scribes. Following the classical humanist typefaces, typographically in the 16th century came the garalde (or old-style) faces, paying homage to Claude Garamond and Aldus Manutius. These featured a heavier weight and stronger emphasis on the downwards strokes than their antecedents (fig. 3). The weight can be attributed to a more oblique axis of the pen; garalde faces in no way loose their humanist elements. Today the best known garaldes faces are Garamond and Bembo, the former of which there are many versions of. Other notable digital renditions include Adobe Garamond, Granjon, Sabon, and Stempel Garamond.

Fig. 3. Left: 72 pt. Centaur, cut by Bruce Rogers in 1912–1914 based on cuts by Nicholas Jenson made in the height of the Venetian Renaissance, 1469; right: 72 pt. Stempel Garamond, a true Garamondian revival by the Stempel Foundry, 1924. It was later digitized by Linotype.

The other Garamond

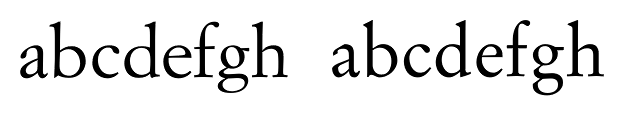

A century after Claude Garamond came Jean Jannon (1580–1658). Jannon was a French Protestant printer who began cutting type in the Protestant Academy in Sedan, France. He cut his type during the French Renaissance but did so illegally under the Catholic regime and consequently had his casts seized in 1641 by agents of the French crown, under orders of Cardinal Richelieu (who ironically used Jannon’s work to later to set his own memoirs, Principaux Points de la Foi). Jannon’s work sat locked-away for two centuries before seeing the light of day again. When they were uncovered they were misidentified as cuts by Claude Garamond, and hence named thereafter Garamond. Many digital revivals still carry on this error: ATF ‘Garamond’, Lanston ‘Garamond’, numerous versions of Monotype ‘Garamond’ and Simoncini ‘Garamond’. Jannon’s work is baroque in nature; it is easily distinguished from Claude Garmond’s; sharper serifs and an almost wild variation of axis and slope (fig. 4, 5).

Fig. 4. Left: 72 pt. Monotype Garamond, digital revival based on Jean Jannon’s cuts; right: 72 pt. Adobe Garamond, digitally revived by Robert Slimbach, based on Claude Garamond’s cuts.

Fig. 5. Left: 72 pt. Simonici Garamond, another digital revival based on Jean Jannon’s cuts; right: 72 pt. Stempel Garamond again, based on Claude Garamond’s cuts.

Historically befitting

So if you’re writing a piece on the introduction of French printing and want to set it in an appropriate typeface, a Garamond revival is most apt — of course you could pick a heavy gothic with which Johann Heynlin and Guillaume Fichet began France’s printing ventures but no one would comfortably read it today (and ultimately the blackletters are more Germanic than French). Conversely if you’re writing a piece set three centuries later, covering the French Renaisance, select one of Jannon’s revivals and pay tribute to a man almost forgotten by history.